Golap Sundari (1857-1910)

Photo: Natya Shodh Sansthan

Photo: Natya Shodh Sansthan

Golapsundari, later known as Sukumari Dutta, was one of the very first actresses on the Calcutta stage. She made her debut in Michael Madhushudan’s Sharmistha, delivering her first lines in Shakespearean-inspired Bengali blank verse. Her emergence from the anonymity of the red-light district into the spotlight seemed, for a moment, to bring with it the promise of elevation from abhadro (uncivil) to bhadro (civil) womanhood. Golap became ‘Mrs. Dutta’ after marrying a gentleman. Yet despite her marriage, she was never accepted as a bhadromohila. That the decision of the managers of the Bengal Theatre to employ Golap was seen by the public as the result of English influence is suggested by a review in The Indian Mirror of Shakuntala, staged at The Bengal in 1878:

"Lord and Lady Lytton visited the Bengal Theatre on Friday last. We are not going to say anything against the management of this Institution. But considering that the theatre had drawn to itself the prostitutes of Calcutta, who are known to ply their dirty trade openly to the public, and that the practice of employing them as actresses is one that is utterly repugnant to Hindu feeling, Lord Lytton might have paused before taking a step so ill calculated to promote the ends of morality."

The same attitude prevailed in 1893 when The Hindu Patriot of 18 August said ‘we wish this dramatic corps had done without the actresses’ who were pejoratively described as ‘professional women’. The Bharat Samskar also wrote: ‘Till now we had seen prostitutes performing in jatras, dances, kirtans and jumur, but this is the first time men of respectable families have performed publicly with these women’. As in nationalist responses to Shakespeare, ‘western’ immorality becomes a source of societal contamination that is ‘repugnant to Hindu feeling’. The threat to the bhadra household, men of ‘respectable families’, is carried like a disease by women who, despite being Bengali, are ‘foreign’ due to their outcast status, redoubled in its foreignness by working in the ‘Western’ theatre.

The accusations against the Theatre of ‘western’ immorality were compensated for by the staging of nationalist stories of legendary status. Golap earned considerable recognition by playing the idealised women in these stories. Still, she was not accepted into respectable society due to her public and active role in realising these narratives on stage. Two of her most famous roles were Bimala in Bankim’s Durgeshnandini and Queen Aliabala in Jyotrindranath Tagore’s heroic drama, Puru Vikram, both staged c.1894. Golap could not have found more overtly nationalist roles to play—she even excelled in a staged version of Bankim’s Anandamath. Yet her marriage to a gentleman took her attempted transition from whore to angel beyond the realm of the literary and imaginary and into the politics of Bengal’s real-life social arena where it was intolerable. Her husband was forced by the weight of public opinion to leave her and flee to England where he died, leaving the new Mrs. Sukumari Dutta with a small daughter to raise on her own. The couple’s attempt to live respectably was ridiculed in a proverbial ditty:

"A woman of pleasure I am, Sukumari,

Man and Woman, we act it out together,

Come watch us, you people of the world."

Sukumari, however, continued to fight her janmashap (‘ill-birth’) by channelling Shakespearean tragedy into her own responses to society’s judgement on her. She wrote a play called Apurba Sati (Great Sacrifice), staged at the Great National Theatre in 1875. The cover of the autobiographical work proclaims in capital letters 'TRAGEDY! TRAGEDY! TRAGEDY!’ It concerns a prostitute's daughter who makes a vow of true love to a young man whom the mother has arranged for her to marry. The disastrous arrival of a rich guest who offers more for the girl presents the main conflict. The daughter of the house, true to the Shakespearean tragic Love model, dies faithful to her first love. Sukumari’s social commentary, directed particularly to women readers, is most pronounced in the play’s preface. Titled ‘Agradrishti’ (Foresight), it asks:

"Women Readers:

At a sudden glance, a pair of misshapen eyes, when made up beautifully gives pleasure. Why (is that so)? Their only contribution is ornament. But what are the many different kinds of ornaments? The first, that which is apparently delightful to all and the second, that which pleases the gods and feeds the understanding. Light (understanding) which is refracted can never be cause enough for happiness. Sisters! What is the light that you seek? You are educated and progressive: of what kind is the ornament sought by your minds, minds that have been informed by higher learning? The first kind is for the amusement of the self, the second (involves) the world—all three worlds. Then, is it the first that you desire? But no, superior learning surely cannot stoop so low..."

Sukumari implores the educated bhadromohilas of her society to look beyond appearances and see reality, to see through the label of ‘prostitute’ and recognise her humanity. By choosing a domestic drama as an expression of her own heartbreak and destitution, she shows a keen awareness of her own position in the social order and a potential way to gain the sympathies of a female audience who are similarly dependent on males for survival, though not to the same extent. She challenges her readers through the familiar opposition of spiritual Love and the material Lust—in this case the selfish desire for economic, or ‘ornamental’, gain—that governs the popular conception of the prostitute as deceitful and mercenary.

Sukumari showed great initiative in attempting to re-cast her image in the public eye. No doubt the multiplicity of roles she played, facilitated by the influence of Shakespeare on the Calcutta stage, opened her eyes to the possibility of a new identity. However, despite the freedom and relative economic independence provided by powerful roles in the Theatre, her desire for a respectable existence was tied to the ideology of nationalist domesticity. The notion of ‘Sati’ (sacrifice), recurring in the titles of many of the early plays of the commercial theatre next to Sukumari’s own play, reinforces the demand for purity and submissiveness in the ideal Bengali woman. Sukumari harnessed her knowledge of this requirement in an attempt to ‘redeem’ herself through art. On 1 October 1883, she took the bold step of directing an all-female theatre company, the Hindoo Female Theatre, choosing to stage an appropriately mystical drama, Sumba Sanhar. The veil of mythology and spiritualistic warfare channelled a Vivekananda-style nationalism into what was, in reality, a radical display of female agency. The Statesman advertisement was as follows:

"Grand opening night

Hindoo Female Theatre (on stage of National Theatre)

That successful and mythological martial drama

Sumbha Sanhar

Will be played on Monday the 1st and Wednesday the 3rd Oct.

Mrs. Sukumari Dutta

Star of the native stage, manager."

Unfortunately for Sukumari, the Hindoo Female Theatre proved only a short-term endeavour. The performance itself was absorbed within the wider, male-oriented nationalist project. Well into the twentieth century stigma against Bengali actresses of Shakespeare like Golap/Sukumari was being compensated for by their contribution to the nationalist project. On 19 January 1925, a Bengali Hamlet called ‘Hariraj’ was performed by an all-female group called ‘Bhikharini Theatre’ (Female Beggars’ Theatre). The announcement in Nachghar read:

"A theatrical group called “Bhikharini Theatre” will act Hariraj and Hiranmayi on Monday next at the Monmohan Natyamandir. This group consists entirely of women. The proceeds of the show will be used for works of public welfare. It is a good sign that, although they are beyond the pale of society, the hearts of hapless fallen women also respond to the suffering of the country."

Like the Hindoo Female Theatre before them, the ‘hearts’ of the Shakespearean actresses in the Bhikarini Theatre group were valued primarily for their usefulness in expressing ‘the suffering of the country’. Despite the value of their economic contribution, the taint of money excluded these women from the very society their work helped to empower against British authority.

"Lord and Lady Lytton visited the Bengal Theatre on Friday last. We are not going to say anything against the management of this Institution. But considering that the theatre had drawn to itself the prostitutes of Calcutta, who are known to ply their dirty trade openly to the public, and that the practice of employing them as actresses is one that is utterly repugnant to Hindu feeling, Lord Lytton might have paused before taking a step so ill calculated to promote the ends of morality."

The same attitude prevailed in 1893 when The Hindu Patriot of 18 August said ‘we wish this dramatic corps had done without the actresses’ who were pejoratively described as ‘professional women’. The Bharat Samskar also wrote: ‘Till now we had seen prostitutes performing in jatras, dances, kirtans and jumur, but this is the first time men of respectable families have performed publicly with these women’. As in nationalist responses to Shakespeare, ‘western’ immorality becomes a source of societal contamination that is ‘repugnant to Hindu feeling’. The threat to the bhadra household, men of ‘respectable families’, is carried like a disease by women who, despite being Bengali, are ‘foreign’ due to their outcast status, redoubled in its foreignness by working in the ‘Western’ theatre.

The accusations against the Theatre of ‘western’ immorality were compensated for by the staging of nationalist stories of legendary status. Golap earned considerable recognition by playing the idealised women in these stories. Still, she was not accepted into respectable society due to her public and active role in realising these narratives on stage. Two of her most famous roles were Bimala in Bankim’s Durgeshnandini and Queen Aliabala in Jyotrindranath Tagore’s heroic drama, Puru Vikram, both staged c.1894. Golap could not have found more overtly nationalist roles to play—she even excelled in a staged version of Bankim’s Anandamath. Yet her marriage to a gentleman took her attempted transition from whore to angel beyond the realm of the literary and imaginary and into the politics of Bengal’s real-life social arena where it was intolerable. Her husband was forced by the weight of public opinion to leave her and flee to England where he died, leaving the new Mrs. Sukumari Dutta with a small daughter to raise on her own. The couple’s attempt to live respectably was ridiculed in a proverbial ditty:

"A woman of pleasure I am, Sukumari,

Man and Woman, we act it out together,

Come watch us, you people of the world."

Sukumari, however, continued to fight her janmashap (‘ill-birth’) by channelling Shakespearean tragedy into her own responses to society’s judgement on her. She wrote a play called Apurba Sati (Great Sacrifice), staged at the Great National Theatre in 1875. The cover of the autobiographical work proclaims in capital letters 'TRAGEDY! TRAGEDY! TRAGEDY!’ It concerns a prostitute's daughter who makes a vow of true love to a young man whom the mother has arranged for her to marry. The disastrous arrival of a rich guest who offers more for the girl presents the main conflict. The daughter of the house, true to the Shakespearean tragic Love model, dies faithful to her first love. Sukumari’s social commentary, directed particularly to women readers, is most pronounced in the play’s preface. Titled ‘Agradrishti’ (Foresight), it asks:

"Women Readers:

At a sudden glance, a pair of misshapen eyes, when made up beautifully gives pleasure. Why (is that so)? Their only contribution is ornament. But what are the many different kinds of ornaments? The first, that which is apparently delightful to all and the second, that which pleases the gods and feeds the understanding. Light (understanding) which is refracted can never be cause enough for happiness. Sisters! What is the light that you seek? You are educated and progressive: of what kind is the ornament sought by your minds, minds that have been informed by higher learning? The first kind is for the amusement of the self, the second (involves) the world—all three worlds. Then, is it the first that you desire? But no, superior learning surely cannot stoop so low..."

Sukumari implores the educated bhadromohilas of her society to look beyond appearances and see reality, to see through the label of ‘prostitute’ and recognise her humanity. By choosing a domestic drama as an expression of her own heartbreak and destitution, she shows a keen awareness of her own position in the social order and a potential way to gain the sympathies of a female audience who are similarly dependent on males for survival, though not to the same extent. She challenges her readers through the familiar opposition of spiritual Love and the material Lust—in this case the selfish desire for economic, or ‘ornamental’, gain—that governs the popular conception of the prostitute as deceitful and mercenary.

Sukumari showed great initiative in attempting to re-cast her image in the public eye. No doubt the multiplicity of roles she played, facilitated by the influence of Shakespeare on the Calcutta stage, opened her eyes to the possibility of a new identity. However, despite the freedom and relative economic independence provided by powerful roles in the Theatre, her desire for a respectable existence was tied to the ideology of nationalist domesticity. The notion of ‘Sati’ (sacrifice), recurring in the titles of many of the early plays of the commercial theatre next to Sukumari’s own play, reinforces the demand for purity and submissiveness in the ideal Bengali woman. Sukumari harnessed her knowledge of this requirement in an attempt to ‘redeem’ herself through art. On 1 October 1883, she took the bold step of directing an all-female theatre company, the Hindoo Female Theatre, choosing to stage an appropriately mystical drama, Sumba Sanhar. The veil of mythology and spiritualistic warfare channelled a Vivekananda-style nationalism into what was, in reality, a radical display of female agency. The Statesman advertisement was as follows:

"Grand opening night

Hindoo Female Theatre (on stage of National Theatre)

That successful and mythological martial drama

Sumbha Sanhar

Will be played on Monday the 1st and Wednesday the 3rd Oct.

Mrs. Sukumari Dutta

Star of the native stage, manager."

Unfortunately for Sukumari, the Hindoo Female Theatre proved only a short-term endeavour. The performance itself was absorbed within the wider, male-oriented nationalist project. Well into the twentieth century stigma against Bengali actresses of Shakespeare like Golap/Sukumari was being compensated for by their contribution to the nationalist project. On 19 January 1925, a Bengali Hamlet called ‘Hariraj’ was performed by an all-female group called ‘Bhikharini Theatre’ (Female Beggars’ Theatre). The announcement in Nachghar read:

"A theatrical group called “Bhikharini Theatre” will act Hariraj and Hiranmayi on Monday next at the Monmohan Natyamandir. This group consists entirely of women. The proceeds of the show will be used for works of public welfare. It is a good sign that, although they are beyond the pale of society, the hearts of hapless fallen women also respond to the suffering of the country."

Like the Hindoo Female Theatre before them, the ‘hearts’ of the Shakespearean actresses in the Bhikarini Theatre group were valued primarily for their usefulness in expressing ‘the suffering of the country’. Despite the value of their economic contribution, the taint of money excluded these women from the very society their work helped to empower against British authority.

Teenkori Dasi (1870-1917)

Photo: Natyamandir

Photo: Natyamandir

Teenkori Dasi rose to fame in the role of Lady Macbeth and established a tradition of Bengali female tragic actresses by performing the role of Jana—a composite character influenced by Jana from The Mahabharata, Lady Macbeth, Queen Margaret and Volumnia—in the same year (1893). Teenkori’s legacy, however, has been overshadowed by the immense presence of the Girishchandra Ghosh. It is therefore difficult to interpret the extent of Teenkori’s experience of the Shakespearean roles. Yet as Bhattacharya observes, the ‘fine transition from ‘understanding’ a part to incarnating it in person on the stage required sensibility and intellect, while the representation of characters who lived in other worlds separated by barriers of time, gender and class drew on a richness of imagination that is truly enviable. The movement is one from a talented little girl to an outstanding actress.’

Teenkori was working at the City Theatre when Girish discovered her astounding voice, taking her with him to the Minerva Theatre where they were rehearsing his Bengali Macbeth. An established actress named Pramoda Sundari had already been cast as Lady Macbeth but Girish decided that Promoda’s ‘facial expression’ just would not do. Sengupta suggests that ‘Teenkori was particularly suited to play Lady Macbeth with a grave, tragic appearance.’ However, Teenkori’s own reflection on her audition for the role is more concerned with the text and meaning than appearances:

“I came back home with the script. I couldn't sleep at all... I stayed up all night and read the part about eight to ten times and learnt it by heart. I had heard Girish Babu correct Pramoda when she made mistakes ... I remembered her mistakes and learnt to follow his instructions...”

It may seem like Teenkori simply followed instructions, mouthing a text that was beyond her little learning. But actresses like Teenkori participated in regular reading sessions conducted by Girish who explained the subtleties of characters and contextualised their role in the world of the play as well as Shakespeare’s society. Girish was so pleased with Teenkori’s realisation of the character that, after his performance in the title role, he exclaimed, ‘Lady Macbeth has surpassed Macbeth, I cannot possibly keep up with her.’ Critics agreed with Girish on opening night. On 20 February 1893 The Indian Nation remarked:

"It is impossible to say of a Shakespearean play that it has been acted to perfection, but we can say of this play that it was acted very well at the Minerva. The parts that were especially well done were those of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, who has a Mrs. Siddons like appearance."

And so, Teenkori Dasi became ‘The Bengali Siddons’, usurping the title of ‘The Indian Siddons’ from the English Esther Leach before her. It was thus through a role marked by ambition and a violation of hospitality that Teenkori was able to rival her English predecessors in the Bengali psyche. Her performance became a source of authority for the Bengali male author, as Girish remarked, ‘[a]fter watching your performance I feel my writing [of this Bengali Macbeth] has been successful.’ Girish even hoped that Teenkori would author her own creations and be immortalised for her contributions, ‘may you be a true artist, may you perform, so that as long as theatre exists, you will be remembered.’

We cannot know if playing these powerful women who articulated their ambitions and frustrations from within the ‘boxness’ of patriarchal expectation gave voice to any of Teenkori’s own personal struggles. It is tempting to imagine her expressing her anger at being an object of societal scorn, or of relishing the power of Shakespeare’s queens, denied her in real life. We can be certain that Teenkori loved her job and fought hard to continue acting. She told the biographer Upendranath Vidyabhusan that her mother had set her up with a couple of babus who had offered to pay her two hundred rupees per month, on top of her earnings as an actress, if she only ‘gave up theatre’. Often if a prostitute bore a daughter, her mother’s highest hope for her would be to become a babu’s mistress. Teenkori describes the overpowering musk of the babus who came to her house when she was about sixteen. She asks, ‘could a woman like my mother ever resist the temptation of so much money?’ and goes on to narrate how the way the men looked at her made her want to grab them by the throat and throw them out. When she refused to give up acting, her mother beat her and starved her for days, but she remained determined. Teenkori was also very particular about the way she appeared in roles. During a performance of Karameti Bai, where she played a widow, she refused to wear white clothes, the traditional garb of a woman in mourning, on stage. It became apparent that a babu who was ‘keeping’ her at the time was in the audience and she could not appear like a widow when she was ‘married’ to him. Even though the couple were not legally married, Teenkori felt bound to the terms of domestic ideology and the play could not begin until the babu left the theatre.

Teenkori’s volitality in life and her desire not to be the object of babus is reflected in the violent tempestuousness of her tragic roles. Her characters complicated the boundary between a monstrous and hybrid femininity associated with the Western Lady Macbeth and the submissiveness of the ideal bhadramohila through her portrayal of Jana. The similarities between the Scottish and the Indian ladies, unified in the body of Teenkori, reveal the trait of ambition to be forbidden in women of both cultures.

Yet perhaps Teenkori’s eventual disappearance from the limelight shows that her purpose, to usher the Shakespearean into Bengali drama, was useful insofar as it warned viewers against unwomanly ambition, ultimately maintaining traditional conceptions of respectable femininity at the centre of a rising national identity.

Teenkori was working at the City Theatre when Girish discovered her astounding voice, taking her with him to the Minerva Theatre where they were rehearsing his Bengali Macbeth. An established actress named Pramoda Sundari had already been cast as Lady Macbeth but Girish decided that Promoda’s ‘facial expression’ just would not do. Sengupta suggests that ‘Teenkori was particularly suited to play Lady Macbeth with a grave, tragic appearance.’ However, Teenkori’s own reflection on her audition for the role is more concerned with the text and meaning than appearances:

“I came back home with the script. I couldn't sleep at all... I stayed up all night and read the part about eight to ten times and learnt it by heart. I had heard Girish Babu correct Pramoda when she made mistakes ... I remembered her mistakes and learnt to follow his instructions...”

It may seem like Teenkori simply followed instructions, mouthing a text that was beyond her little learning. But actresses like Teenkori participated in regular reading sessions conducted by Girish who explained the subtleties of characters and contextualised their role in the world of the play as well as Shakespeare’s society. Girish was so pleased with Teenkori’s realisation of the character that, after his performance in the title role, he exclaimed, ‘Lady Macbeth has surpassed Macbeth, I cannot possibly keep up with her.’ Critics agreed with Girish on opening night. On 20 February 1893 The Indian Nation remarked:

"It is impossible to say of a Shakespearean play that it has been acted to perfection, but we can say of this play that it was acted very well at the Minerva. The parts that were especially well done were those of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, who has a Mrs. Siddons like appearance."

And so, Teenkori Dasi became ‘The Bengali Siddons’, usurping the title of ‘The Indian Siddons’ from the English Esther Leach before her. It was thus through a role marked by ambition and a violation of hospitality that Teenkori was able to rival her English predecessors in the Bengali psyche. Her performance became a source of authority for the Bengali male author, as Girish remarked, ‘[a]fter watching your performance I feel my writing [of this Bengali Macbeth] has been successful.’ Girish even hoped that Teenkori would author her own creations and be immortalised for her contributions, ‘may you be a true artist, may you perform, so that as long as theatre exists, you will be remembered.’

We cannot know if playing these powerful women who articulated their ambitions and frustrations from within the ‘boxness’ of patriarchal expectation gave voice to any of Teenkori’s own personal struggles. It is tempting to imagine her expressing her anger at being an object of societal scorn, or of relishing the power of Shakespeare’s queens, denied her in real life. We can be certain that Teenkori loved her job and fought hard to continue acting. She told the biographer Upendranath Vidyabhusan that her mother had set her up with a couple of babus who had offered to pay her two hundred rupees per month, on top of her earnings as an actress, if she only ‘gave up theatre’. Often if a prostitute bore a daughter, her mother’s highest hope for her would be to become a babu’s mistress. Teenkori describes the overpowering musk of the babus who came to her house when she was about sixteen. She asks, ‘could a woman like my mother ever resist the temptation of so much money?’ and goes on to narrate how the way the men looked at her made her want to grab them by the throat and throw them out. When she refused to give up acting, her mother beat her and starved her for days, but she remained determined. Teenkori was also very particular about the way she appeared in roles. During a performance of Karameti Bai, where she played a widow, she refused to wear white clothes, the traditional garb of a woman in mourning, on stage. It became apparent that a babu who was ‘keeping’ her at the time was in the audience and she could not appear like a widow when she was ‘married’ to him. Even though the couple were not legally married, Teenkori felt bound to the terms of domestic ideology and the play could not begin until the babu left the theatre.

Teenkori’s volitality in life and her desire not to be the object of babus is reflected in the violent tempestuousness of her tragic roles. Her characters complicated the boundary between a monstrous and hybrid femininity associated with the Western Lady Macbeth and the submissiveness of the ideal bhadramohila through her portrayal of Jana. The similarities between the Scottish and the Indian ladies, unified in the body of Teenkori, reveal the trait of ambition to be forbidden in women of both cultures.

Yet perhaps Teenkori’s eventual disappearance from the limelight shows that her purpose, to usher the Shakespearean into Bengali drama, was useful insofar as it warned viewers against unwomanly ambition, ultimately maintaining traditional conceptions of respectable femininity at the centre of a rising national identity.

Tara Sundari (1878-1948)

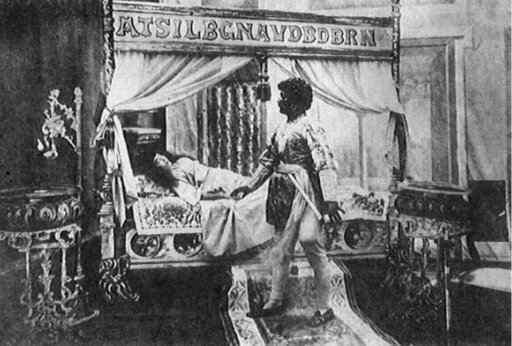

Tara Sundari as Desdemona and Taraknath Palit as Othello, Star Theatre, Calcutta 1919 (Same year as Amritsar). Photo: Internet Shakespeare Editions

Tara Sundari as Desdemona and Taraknath Palit as Othello, Star Theatre, Calcutta 1919 (Same year as Amritsar). Photo: Internet Shakespeare Editions

In Debjani Sengupta’s opinion, Tarasundari ‘infused every role she played with a touch of the sublime. She was a poet […] and she gave every character that she portrayed a poetic dimension.’ What does Sengupta mean by ‘sublime’? In Tara’s various Shakespearean roles, she achieved ground-breaking status. Yet her poetry revokes this life and seeks a different kind of sublimity—one that is sacrosanct and that endorses social norms. Her life is marked by oscillation between the theatre and religious retreat. The tensions of this split-devotion highlight the instability of her position in society, a precariousness which at once endangered her and simultaneously allowed her to speak from spaces inaccessible to the bhadramohila.

Tara inherited the tradition of Bengali female tragedian from Teenkori, starring as Jana (1925) and being measured up against Lady Macbeth in her role as Manmohan Roy’s Queen Reziya (1905). The contemporary Bengali reviewer, Bipin Chandra Pal, described her performance thus:

"But not merely in the refinement and the delicacy … but equally … in the quality of their art, some of our actresses could well hold their own in competition with the best representatives of the English stage. Those who have seen the part of Reziya as it is played by Sreemati Tarasundari, will bear out the truth of this statement. Reziya’s is one of the most complex characters met with in any literature. Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth is possibly a shade simpler than Reziya. And Tara’s rendering of Reziya has been declared by competent critics, who have seen the best European actresses, to be as good an achievement as the best rendering of Lady Macbeth by the most capable of English actresses."

Once again, Shakespeare’s Bengali hostess finds herself in competition with the English. As a respresentative of nationalist response, she must perform with the ‘refinement and delicacy’ ascribed to India’s ancient sophistication. The comparison with ‘the most capabable of English actresses’ is still haunted by the anxiety of influence. Tara is Bengal’s defense against The Englishman’s acerbic remark that a Bengali has received Shakespeare well, ‘for a native’. The purity of Bengali womanhood is an important counter in this position. The Amrita Bazar Patrika introduced ‘Rezia the “Virgin” Queen of histrionic grandeur, comingled with literary culture, and elevating corrections in the shape of chaste honour’. The ‘“Virgin” Queen’ provides a Bengali counterpart to Shakespeare’s Elizabeth I. But the peculiar emphasis on chastity, signalled by the speech marks around ‘“Virgin”’, the inclusion of ‘chaste honour’, and the crude pun at the end of the advertisement, ‘…Rezia to be had at the Box Office,’ was clearly a dig at Tara’s ‘unchaste’ profession. The convenient split between Tara’s role and reality maintains the misogynist polarity between the bhadramohila and the outcast.

Tara began acting in 1884 at the Star Theatre in a small boy’s role in Girish’s play about a saint, Chaitanya Lila. In 1896, she moved to the Classic Theatre, managed by Amarendranath Datta (1876-1916), starring as Ophelia in his Bengali version of Hamlet, Hariraj (1896). Come 1913, Tara was receiving accolades for roles like Cleopatra at the Minerva Theatre. The production starred Girish’s son, Surendranath Ghosh (1868-1932), as Antony, and was advertised as having ‘new princely costumes and superb sceneries made in accordance with Western Ideals.’ The capitalised ‘Western Ideals’ likely refers to the realism of both the set and Tara’s portrayal. The roles played by Shakespeare’s Cleopatra herself—seductress and public figure—actually mirror the labels given to Tara and other prostitute-actresses as sexualised outsiders, threatening to contaminate from the fringes of society the authentic and pure Bengaliness within. Where the imperialist gaze works to conquer Indian society by framing it as Other, Indian constructions of ‘the West’ also manifest here as Bengali society peers through the proscenium arch at an outcast paradoxically playing Shakespeare’s ‘Eastern star’. The effect is sublime as the ‘power’ of Tara’s performances was received with wonder and awe. On 15 March 1919, The Bengalee praised Tara’s performance as Desdemona:

"We were assured by more than one critic that the acting of Desdemona approached perfection and the heroine had shown a remarkable power of adaptability which extorted unstinted praise from the audience".

It was remembered in 1944 by a critic who argued that ‘none of the parts except that of Tarasundari was done to the spirit of the dramatist’. Occidentalism perhaps even manifests here at the level of the set, pictured above, in which garbled letters of uncertain meaning seem to signify ‘Englishness’ in their assemblage above Desdemona’s bed.

Tara’s powers were obscured by the overbearing presence of the ‘fathers’ of the theatre world. She was caught in a struggle for the title of ‘Garrick of the Bengali Stage’ between Girish Ghosh and Amarendranath Datta. After Girish’s Macbeth proved unpopular, reviews of Dutta’s Harijaj, starring Tara as Ophelia, began to refer to him as the Bengali Garrick. Girish had trained Datta and the threat to the father-figure’s authority was met by a spiteful judgement on the pupil’s work. Girish printed a caricature of Datta in the newspaper with the following caption:

"Our representation, we feel bold to say, will prove to “them” that howling is not acting, and that such a subject, at once serious and sublime, ought not to be handled by quacks who will unscrupulously lay their hands on the most complicated cases without possessing the requisite qualification of even a common place amateur."

Shakespeare as a ‘serious and sublime’ subject should have, in Girish’s opinion, received a relatively conservative rendition, as in his Scottish-style Macbeth, as opposed to Datta’s Indianised Hariraj. More than this, however, Girish’s spite was fuelled by Tara’s affair with Datta, a liaison that caused her to leave Girish’s Star, albeit briefly, to live in a baganbari set up for her by Datta. For Tara, the affair was disastrous. Datta proved financially unwise, spending his life in debt and litigation—some of the legal problems being a direct result of the affair. Girish took Datta back under his wing after the latter was declared bankrupt. Nevertheless, the damage to Tara’s reputation was done.

Tara’s association with Datta did at least jumpstart her career as a Shakespearean actress and provide a venue for her own poetry. Datta edited two journals, Rangalaya and Saurabh. Tara’s poems were printed in the latter. The couplets of her Kusum o Bhramar (The Blossom and the Honey Bee) sting with a highly moralistic self-reproach, as though the power of poetry might cleanse her of a sinful life:

"Like to a woman's youth is your pride:

There will be love for as long as there is honey.

How carelessly did you give away your honour!

How little you knew the ways of this wily world!"

As in Bankim’s reading of Desdemona, Tara transforms herself into a tragic victim whose experience of the injustice ‘of this wily world’ plants the ‘seed of human education’. Tara, only seventeen at the poem’s publication, has been aged by the theatre-world, learning that ‘youth’ is ‘pride’ and beauty the ‘honey’ that is lost without ‘honour’. She exercises what Aurobindo would call a ‘masculine genius’ by appropriating a spiritual rhetoric, common to nationalist discourse. Using the sublimity of religious transcendence, Tara crafts a new identity for herself, emerging phoenix-like from Calcutta’s hellish underworld:

"My life is a burning ground. I'd thought it was Paradise.

Gone are my sins now; New-born are my eyes."

The promises of babus have proved a false ‘Paradise’ for the ‘New-born’ Tara. She is the blossom, tragically polluted by the corruption of society. This is a familiar story except that Tara has reversed the source of pollution. It is not she, the prostitute-actress, who has threatened to contaminate the essence of Bengali culture, but Bengali society, particularly male customers and voyeurs, who have robbed her of her purity. She exposes the demarcation between ‘bad’ women and ‘good’ bhadrolok (civil-men) as a piece of theatrical artifice:

"We are hated by society. In our lives, being “bad” has a big role to play. We come to the theatre and give up the “bad.” You are Bhadralok. You come here and give up some of your “good”. We together collect the “good” you leave behind, and you take back the “bad” of our nature."

Till her last days, Tara turned the Manicheanism of her society on its head. By becoming a poet, Tara took on a traditionally masculine role in an attempt to reclaim her innocence. In reality, however, such a transaction could not survive. Tara was forced because of financial circumstances to return to the underworld that was the commercial theatre, despite repeated attempts to escape to a religious existence after her son’s death in 1922. Even after she finally retired to an ashram in Bhuvaneshwar, babus continued to proposition the stigmatised actress.

For welcoming Shakespeare as one of his first Bengali hostesses, Tara was cast out of the ‘house’ of Bengali society. As Bhattacharya observes:

"The stage was, in fact, the only place where the actress really belonged, but it was ultimately a world of make believe. ‘Home’, as it was inscribed in the conventional value system, was out of bounds for the actresses and invariably their efforts at sansar had an unhappy ending. Their writings were, therefore, located in an alternative sphere in an effort to break through the mutually exclusive realm of the home and the world."

Domestic life or, ‘sansar’, was to be desired but also dreaded. Prostitute-actresses were denied the protection of the traditional home but this denial also allowed an escape from its physical confines. They gained access to money and fame beyond the dreams of the bhadramohila and could write and perform alongside men. However, they were still bound to the polarities of domestic ideology and the ‘alternative sphere’ created by their performances and writings could only subvert these oppositions to a figurative extent. The prestige of high culture, made available in their encounters with Shakespeare, offered a fleeting kind of protection.

It is unsurprising that many of these actresses sought the sanctuary of religious life, given that the alternatives for older actresses were sparse. Tara could easily have suffered the same fate as the only contemporary Bengali actress who we have recorded playing Shakespeare in English, Kusum Kumari. Kusum’s performance as Lady Macbeth in 1917 was celebrated by the Amrita Bazar Patrika; ‘The rendering of a Shakespearean scene in original English by a Bengali actress is a wonderful thing.’ Yet Kusum was found begging on the street in 1945. Despite the threats of imprisonment as a domestic slave to a wealthy patron, or the spiritual degradation Tarasundari felt to be the result of a life as both a prostitute and an actress, her career as a famed Shakespearean performer allowed her to temporarily challenge the conceptual flow of pollution within Bengali society. She recognises, perhaps due to her understanding of the theatre, that ‘bad’ is a role in which she has been cast and that notions of purity in bhadra society depend on her playing the part well. The threat posed by the sublime guest from outside the Home to the internal essence of Bengali culture is shown, in Tarasunadri’s writing, to be a disease already existing at the heart of domestic ideology that necessitates an Other. Shakespeare played a key role in mediating this complex and perception within Bengali domestic ideology as a source of cultural value and prestige.

Tara inherited the tradition of Bengali female tragedian from Teenkori, starring as Jana (1925) and being measured up against Lady Macbeth in her role as Manmohan Roy’s Queen Reziya (1905). The contemporary Bengali reviewer, Bipin Chandra Pal, described her performance thus:

"But not merely in the refinement and the delicacy … but equally … in the quality of their art, some of our actresses could well hold their own in competition with the best representatives of the English stage. Those who have seen the part of Reziya as it is played by Sreemati Tarasundari, will bear out the truth of this statement. Reziya’s is one of the most complex characters met with in any literature. Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth is possibly a shade simpler than Reziya. And Tara’s rendering of Reziya has been declared by competent critics, who have seen the best European actresses, to be as good an achievement as the best rendering of Lady Macbeth by the most capable of English actresses."

Once again, Shakespeare’s Bengali hostess finds herself in competition with the English. As a respresentative of nationalist response, she must perform with the ‘refinement and delicacy’ ascribed to India’s ancient sophistication. The comparison with ‘the most capabable of English actresses’ is still haunted by the anxiety of influence. Tara is Bengal’s defense against The Englishman’s acerbic remark that a Bengali has received Shakespeare well, ‘for a native’. The purity of Bengali womanhood is an important counter in this position. The Amrita Bazar Patrika introduced ‘Rezia the “Virgin” Queen of histrionic grandeur, comingled with literary culture, and elevating corrections in the shape of chaste honour’. The ‘“Virgin” Queen’ provides a Bengali counterpart to Shakespeare’s Elizabeth I. But the peculiar emphasis on chastity, signalled by the speech marks around ‘“Virgin”’, the inclusion of ‘chaste honour’, and the crude pun at the end of the advertisement, ‘…Rezia to be had at the Box Office,’ was clearly a dig at Tara’s ‘unchaste’ profession. The convenient split between Tara’s role and reality maintains the misogynist polarity between the bhadramohila and the outcast.

Tara began acting in 1884 at the Star Theatre in a small boy’s role in Girish’s play about a saint, Chaitanya Lila. In 1896, she moved to the Classic Theatre, managed by Amarendranath Datta (1876-1916), starring as Ophelia in his Bengali version of Hamlet, Hariraj (1896). Come 1913, Tara was receiving accolades for roles like Cleopatra at the Minerva Theatre. The production starred Girish’s son, Surendranath Ghosh (1868-1932), as Antony, and was advertised as having ‘new princely costumes and superb sceneries made in accordance with Western Ideals.’ The capitalised ‘Western Ideals’ likely refers to the realism of both the set and Tara’s portrayal. The roles played by Shakespeare’s Cleopatra herself—seductress and public figure—actually mirror the labels given to Tara and other prostitute-actresses as sexualised outsiders, threatening to contaminate from the fringes of society the authentic and pure Bengaliness within. Where the imperialist gaze works to conquer Indian society by framing it as Other, Indian constructions of ‘the West’ also manifest here as Bengali society peers through the proscenium arch at an outcast paradoxically playing Shakespeare’s ‘Eastern star’. The effect is sublime as the ‘power’ of Tara’s performances was received with wonder and awe. On 15 March 1919, The Bengalee praised Tara’s performance as Desdemona:

"We were assured by more than one critic that the acting of Desdemona approached perfection and the heroine had shown a remarkable power of adaptability which extorted unstinted praise from the audience".

It was remembered in 1944 by a critic who argued that ‘none of the parts except that of Tarasundari was done to the spirit of the dramatist’. Occidentalism perhaps even manifests here at the level of the set, pictured above, in which garbled letters of uncertain meaning seem to signify ‘Englishness’ in their assemblage above Desdemona’s bed.

Tara’s powers were obscured by the overbearing presence of the ‘fathers’ of the theatre world. She was caught in a struggle for the title of ‘Garrick of the Bengali Stage’ between Girish Ghosh and Amarendranath Datta. After Girish’s Macbeth proved unpopular, reviews of Dutta’s Harijaj, starring Tara as Ophelia, began to refer to him as the Bengali Garrick. Girish had trained Datta and the threat to the father-figure’s authority was met by a spiteful judgement on the pupil’s work. Girish printed a caricature of Datta in the newspaper with the following caption:

"Our representation, we feel bold to say, will prove to “them” that howling is not acting, and that such a subject, at once serious and sublime, ought not to be handled by quacks who will unscrupulously lay their hands on the most complicated cases without possessing the requisite qualification of even a common place amateur."

Shakespeare as a ‘serious and sublime’ subject should have, in Girish’s opinion, received a relatively conservative rendition, as in his Scottish-style Macbeth, as opposed to Datta’s Indianised Hariraj. More than this, however, Girish’s spite was fuelled by Tara’s affair with Datta, a liaison that caused her to leave Girish’s Star, albeit briefly, to live in a baganbari set up for her by Datta. For Tara, the affair was disastrous. Datta proved financially unwise, spending his life in debt and litigation—some of the legal problems being a direct result of the affair. Girish took Datta back under his wing after the latter was declared bankrupt. Nevertheless, the damage to Tara’s reputation was done.

Tara’s association with Datta did at least jumpstart her career as a Shakespearean actress and provide a venue for her own poetry. Datta edited two journals, Rangalaya and Saurabh. Tara’s poems were printed in the latter. The couplets of her Kusum o Bhramar (The Blossom and the Honey Bee) sting with a highly moralistic self-reproach, as though the power of poetry might cleanse her of a sinful life:

"Like to a woman's youth is your pride:

There will be love for as long as there is honey.

How carelessly did you give away your honour!

How little you knew the ways of this wily world!"

As in Bankim’s reading of Desdemona, Tara transforms herself into a tragic victim whose experience of the injustice ‘of this wily world’ plants the ‘seed of human education’. Tara, only seventeen at the poem’s publication, has been aged by the theatre-world, learning that ‘youth’ is ‘pride’ and beauty the ‘honey’ that is lost without ‘honour’. She exercises what Aurobindo would call a ‘masculine genius’ by appropriating a spiritual rhetoric, common to nationalist discourse. Using the sublimity of religious transcendence, Tara crafts a new identity for herself, emerging phoenix-like from Calcutta’s hellish underworld:

"My life is a burning ground. I'd thought it was Paradise.

Gone are my sins now; New-born are my eyes."

The promises of babus have proved a false ‘Paradise’ for the ‘New-born’ Tara. She is the blossom, tragically polluted by the corruption of society. This is a familiar story except that Tara has reversed the source of pollution. It is not she, the prostitute-actress, who has threatened to contaminate the essence of Bengali culture, but Bengali society, particularly male customers and voyeurs, who have robbed her of her purity. She exposes the demarcation between ‘bad’ women and ‘good’ bhadrolok (civil-men) as a piece of theatrical artifice:

"We are hated by society. In our lives, being “bad” has a big role to play. We come to the theatre and give up the “bad.” You are Bhadralok. You come here and give up some of your “good”. We together collect the “good” you leave behind, and you take back the “bad” of our nature."

Till her last days, Tara turned the Manicheanism of her society on its head. By becoming a poet, Tara took on a traditionally masculine role in an attempt to reclaim her innocence. In reality, however, such a transaction could not survive. Tara was forced because of financial circumstances to return to the underworld that was the commercial theatre, despite repeated attempts to escape to a religious existence after her son’s death in 1922. Even after she finally retired to an ashram in Bhuvaneshwar, babus continued to proposition the stigmatised actress.

For welcoming Shakespeare as one of his first Bengali hostesses, Tara was cast out of the ‘house’ of Bengali society. As Bhattacharya observes:

"The stage was, in fact, the only place where the actress really belonged, but it was ultimately a world of make believe. ‘Home’, as it was inscribed in the conventional value system, was out of bounds for the actresses and invariably their efforts at sansar had an unhappy ending. Their writings were, therefore, located in an alternative sphere in an effort to break through the mutually exclusive realm of the home and the world."

Domestic life or, ‘sansar’, was to be desired but also dreaded. Prostitute-actresses were denied the protection of the traditional home but this denial also allowed an escape from its physical confines. They gained access to money and fame beyond the dreams of the bhadramohila and could write and perform alongside men. However, they were still bound to the polarities of domestic ideology and the ‘alternative sphere’ created by their performances and writings could only subvert these oppositions to a figurative extent. The prestige of high culture, made available in their encounters with Shakespeare, offered a fleeting kind of protection.

It is unsurprising that many of these actresses sought the sanctuary of religious life, given that the alternatives for older actresses were sparse. Tara could easily have suffered the same fate as the only contemporary Bengali actress who we have recorded playing Shakespeare in English, Kusum Kumari. Kusum’s performance as Lady Macbeth in 1917 was celebrated by the Amrita Bazar Patrika; ‘The rendering of a Shakespearean scene in original English by a Bengali actress is a wonderful thing.’ Yet Kusum was found begging on the street in 1945. Despite the threats of imprisonment as a domestic slave to a wealthy patron, or the spiritual degradation Tarasundari felt to be the result of a life as both a prostitute and an actress, her career as a famed Shakespearean performer allowed her to temporarily challenge the conceptual flow of pollution within Bengali society. She recognises, perhaps due to her understanding of the theatre, that ‘bad’ is a role in which she has been cast and that notions of purity in bhadra society depend on her playing the part well. The threat posed by the sublime guest from outside the Home to the internal essence of Bengali culture is shown, in Tarasunadri’s writing, to be a disease already existing at the heart of domestic ideology that necessitates an Other. Shakespeare played a key role in mediating this complex and perception within Bengali domestic ideology as a source of cultural value and prestige.

Binodini Dasi (1863-1941)

Girish Chandra Ghosh and Binodini during a performance. Photo: https://www.tutorialathome.in/history/nati-binodini-houses-calcutta

Girish Chandra Ghosh and Binodini during a performance. Photo: https://www.tutorialathome.in/history/nati-binodini-houses-calcutta

"Binodini Dasi is the most famous nineteenth-century Bengali actress and remains a cult figure, ‘Nati Binodini’, in numerous re-enactments of her life today. Unfortunately there is no extant direct evidence of Binodini in a Shakespeare play. However it is highly likely that Binodini did play a Shakespearean character, especially in the period before she became famous, for which the records are even scarcer. Nevertheless, it is clear that exposure to and digesting of Shakespeare was a crucial element in forming her sensibility and technique as an actress.

We do know that she played Kalpalkundala, Bankim Chattopadhyay’s Miranda/Desdemona composite, and we have her pictured ‘in the role of Cleopatra’ (as seen in the top photo heading this page). Binodini was also a prolific writer, unique in that she left detailed descriptions of the process of acting, including the impact of Shakespeare on her craft—though not explicitly through playing a role. Rimli Bhattacharya’s translations of Binodini’s Amar Katha (My Story, 1912) and Amar Abhinitri Jiban (My Life as an Actress, 1924-25) are invaluable resources for tracing this influence. Binodini’s only education came through the theatre. Binodini’s recollections illustrate the role of Shakespeare in the relationship between director and actress:

"I liked very much the stories narrated by Girish-babu about famous British actors and actresses and whatever else he read out to us from books: He explained to us the various kinds of critical opinions expressed about Mrs. Siddons when she had rejoined the theatre after being married for ten years. He even told us of an actress in England who practised her notes with the birds in the forest. I was also told about the costume that Ellen Terry wore; how Bandmann dressed in his role as Hamlet; how Ophelia always wore a dress made of flowers. [He would] talk to us about numerous English actresses and the works of famous English poets such as Shakespeare, Byron, Milton and Pope. He discussed their works in the form of stories and sometimes he read out sections from the texts to explain them better. […] I would be anxious to see the performances of any famous British actor or Actress who happened to come to the city. […] When I came back home after the performances, Girish-babu would say, “Well now, let’s hear something about what you’ve seen.”

We see the actress’s delight, as a pupil, in being introduced to Shakespeare’s ‘stories’ but also her anxiety about performing roles in the ‘English’ way. Mrs. Siddons appears yet again in the psyche of the Bengali hostess as a model of perfection but this time as a warning against leaving the theatre in pursuit of domestic life. Most importantly, the reflection reveals the fact that Binodini was respected enough by her mentor to be asked her opinion on Shakespearean performances. Binodini was invited to view and review the work of the ‘greatest’ poet played by the English masters of her Bengali masters. Such power fuels the traversal of the threshold between actress and writer. Contact with Shakespeare facilitates Binodini’s trajectory from the realm of female object into that of masculine authority.

Binodini relished the ‘power’ and ‘intoxication’ of life on the Bengali Shakespearean stage. Binodini’s description of her first encounter with the stage reverberates with an almost sexual ecstasy:

"When I saw before me the rows of shining lights, and the eager excited gaze of a thousand eyes, my entire body became bathed in sweat, my heart began to beat dreadfully, my legs were actually trembling and it seemed to me that the dazzling scene was clouding over before my eyes. […] Along with fear, anxiety and excitement, a certain eagerness too appeared to overwhelm me. How shall I describe this feeling?"

Binodini was at first overwhelmed by the sublimity of the ‘dazzling’ lights ‘clouding over’ her. However, from her position after the end of her career, in a place of isolation and poverty, the memories of the Theatre have become both her ‘closest companion to the last days of [her] life’ and an ‘addiction’ that she struggles to describe:

"Well, I have the desire. But what powers do I possess? And what shall I speak of? What to say and what not to? How little I know! From time to time I come to see performances. What an addiction it is! As if the theatre beckons to me from the midst of all other work. I look at all the new actors and actresses, educated, refined and elegant, so many new plays, the spectators, the applause, the commotion, the hubbub and the footlights. One scene follows another and the bell rings as the curtain falls—all this and so much more comes back to my mind!"

Like Bengal’s silent coconut groves leaning towards the powerful sun, she is drawn to the memory of the stage by ‘desire’. She embraces the ‘addiction’ that is the theatre, welcoming the deflowering ‘gaze of a thousand eyes’. Her powerful literary description carries with it all the tumult of the ‘the applause, the commotion, the hubbub’ of the moment when ‘the bell rings and the curtain falls’. Despite the effectiveness of her writing, she questions ‘what powers do I possess?’ The guilt of abandoning ‘all other work’, including respectable, private, and silent service to society, in order to describe her ‘addiction’ is expressed through a deep anxiety about both the moral implications of her profession and her supposed inadequacy as a writer. As Bhattacharya observes, Binodini calls her story a ‘narrative of pain’ due to its content as well as the frustrating process of putting ‘ink’ to ‘paper’. Writing, unlike acting, is uncharted territory for the public woman and the process of navigation is agonising at times. A tragic femininity appears in Binodini’s construction of herself as an ‘addict’ and a victim of public life, limited in her writing by her status as an abhadra woman but powerful in her trangressions onto the stage and page.

The tension between Binodini’s transgression of gender-roles and the imposing borders of the male picture-frame is encapsulated by her embodiment of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra. Like Binodini, Cleopatra has been called a ‘supreme actress’, playing the roles of both exotic seducer and faithful wife. Binodini’s known parts ranged from Brittania herself to stereotypical Hindu wives. She was at the centre of a tug-of-war between different femininities—at one end, the westernised prostitute, and at the other, the Hindu domestic fairy. She describes the contradictions of her existence and the confusion it caused her when forming her own identity. On playing the ‘lady of gold’, Kanchan, who seduces the married protagonist of Sadhabar Ekadoshi at the same time as the innocent victim, Kunda, from Bankim's Bishbriksha, she writes:

"What a world of difference (between the two roles) whether in terms of their nature or in terms of the dramatic action. It would be impossible to describe the innumerable selves into which one must divide oneself while acting. As soon as one brought to completion a particular bhava, one was obliged to immediately summon another. This had become natural to me. Even when I was not acting, I would forever be immersed in a different bhava."

In Sadhabar Ekadoshi, the cheating husband’s wife is described as ‘a fairy at home’ and ‘such a precious Sita at home’. The man describes Kanchan as her material and sensual opposite; ‘I’ve put Kanchan-moni, the chief thing in town, on my crown.’ Binodini’s rapid shifts between the bhavas of angel and whore mirror those of Cleopatra who is sometimes a foreign object, sometimes the goddess Isis, and sometimes “no more than e’en a woman”. Cleopatra, as a ruler, is a public woman, trespassing into the realm of masculine authority. A similar array of roles multiply for Binodini as she takes up the male author’s pen and tries to define herself.

Binodini’s final position as a confused social anomaly directly opposes the temporary comfort of social acceptance Binodini attained at the height of her career, when she was blessed by one of Bengal’s most influential religious men while playing a man’s role. In 1884, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda’s guru and one of the most famous saints of the nineteenth-century, visited the Star Theatre. Binodini was playing the role of Chaitanya, an ancient saint whose name means ‘Consciousness’. Binodini describes an encounter between herself and Ramakrishna that made Bengali history:

"it was during this performance of Chaitanya-Lila, that is to say, not only this performance, but the incident around it which became the source of greatest pride in all my life, that I a sinner, was granted grace by the Pramahansadeb SriRamakrishna mahashoy. Because it was after seeing me perform in Chaitanya-Lila, that the most divine of beings granted me refuge at his feet. […] cleansing with his touch my sinful body, he blessed me, “Ma, may you have Chaitanya!” Poignant indeed was the sight of his gentle and compassionate image before an inferior creature such as myself. The Patitpaban himself was reassuring me, but alas, I am truly unfortunate; even so I have been unable to recognise him. Once again, I have been ensnared by temptation and illusion and made my life a veritable hell."

By calling Binodini ‘Ma’, Ramakrishna asserts his view that all women are mothers and ‘cleanses’ her of sexual pollution. Yet the blessing, ‘may you have Chaitanya’ welcomes her into the realm of male reason. By playing the role of a male saint, Binodini was able to approach this power in a socially sanctified manner. The emphasis on her role as a chaste Hindu was so intense that Binodini ‘unsexed’ herself, both by becoming a man on-stage and by intellectually duplicating Ramakrishna’s ideology.

The transformation was, however, only temporary and firmly in the hands of male viewers and benefactors. Binodini’s guilt at having once again become ‘ensnared by temptation and illusion’ refers to her status at the time of writing as a poor woman. Having been thrown out of her house after her husband’s death, Binodini had to return to the ‘sin’ of commerce to survive. Paradoxically, Binodini becomes a virginal mother-figure through male impersonation, an act of transvestism that Cleopatra also uses to exercise authority. While Cleopatra’s rebellious transvestism recalls the monstrous hybridity of Lady Macbeth and prostitution, Binodini’s role is sanitised by the fact of Girish’s influence, Ramakrishna’s praise, and the spiritual character of Chaitanya. The play depicts Chaitanya’s renunciation of the domestic sphere in pursuit of an even more ideologically restricted space of religious retreat. Binodini’s controversial status as a prostitute-actress made the ancient virtues of sacrifice and godliness that Chaitanya represents exciting and new, achieving on stage what Bankim had achieved in his Miranda/Desdemona composite in Kapalkundala.

Yet Binodini’s transcendence of gender and the material world only strengthened Bengali nationalist conceptions of ideal femininity as her existence as an abhadra woman was momentarily erased and replaced by a spiritual image of Bengaliness. Binodini sacrificed her identity for the benefit of an audience who, despite achieving coherence as a group due to such performances of Bengali culture, ultimately were not willing or able to grant the actress equal status in their society. The transformation of Binodini into an eternal image did nothing to elevate her or her colleagues in her lifetime and she continued to experience the pain of a contradictory experience in the ‘veritable hell’ of life after her husband’s death. While the cross-dressing in which the male authors of Part One metaphorically engaged lives on today as integral to notions of Bengali femininity, Binodini’s role as a man remains an odd example, in which the beneficence of the male Ramakrishna is privileged above the actress’ self-proclaimed wretchedness.

The central tragedy of Binodini’s life, which informs the grief behind her ‘narrative of pain,’ is the death of her eleven-year-old daughter, whom she hoped would grow to become an educated young lady. The trauma of failing to raise her daughter was compounded by the fact that she was financially exploited by the Star Theatre. The Star was, in fact, supposed to be named the ‘B theatre’, in recognition of Binodini’s immense contributions to its success. At a time of financial difficulty, Binodini even agreed to be the mistress of a businessman, Gurmukh Rai, in exchange for his investment in Girish’s theatre. Binodini did not receive her promised shares in the company and Girish, fearing that a theatre named after a prostitute-actress would be too confronting, named it the Star. Bhattacharya notes that the ‘inevitable reliance on ‘father figures’ from the theatre world for artistic and material advancement’ explains why Binodini did not question Girish’s judgement, remarking, ‘I had sacrificed what I did for my own sake, no one had compelled me to do so.’ Yet the ghost of Binodini’s daughter, whom she named Shakuntala, haunts the actress’ writing. One of Binodini’s poems, titled Shakuntala, uses Kalidasa’s story to express her own sense of betrayal. The second half of Binodini’s poem reads:

"The creeping vines

balmy wind and flowers

rose and malati, the encircling green and all the birds

who make the air their home

our witnesses be.

Laughter of stars and moonbeams enclosed

In a lover’s kiss.

In return take my body,

My self,

Life itself.

Here lies

The bank where we lay

The same flowers wild,

But where

the shining eyes,

lips smiling?

Why are bright eyes

cast down this day?"

The poem appears in a collection of verse called Basana (Desire), dedicated to Binodini’s mother. Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, used in nationalist responses to Shakespeare to confirm patriarchal notions of femininity, is seized upon by Binodini in constructing a matrilineal line from mother to daughter to grand-daughter. The moment where hospitality fails and King Dushmyanta, eyes down-cast, rejects his hostess-bride becomes symbolic of Bindoni’s personal betrayals. The promised transaction that Binodini would receive compensation and protection in exchange for her services to the theatre is forgotten, witnessed only by the ‘creeping vines / balmy wind and flowers’, and the ‘birds’ who, like Binodini, are outside society and ‘make the air their home’.

The social critique sublimated into the lofty rhetoric of Binodini’s poetry is elsewhere clearly spelled out:

"A prostitute’s life is certainly tainted and despicable; but where does the pollution come from? […] Who are all these men? Are there not some among them who are respected and adored in society? Those who show hatred when in the company of others, but secretly, away from the eyes of men, pretend that they are the best of lovers […] Who is at fault? Those women who have drunk the poison believing it to be nectar and who suffer the torments of their heart for the rest of their lives—are they to blame?"

Like Tarasundari, Binodini conceives the prostitute-actress’ existence in terms of contamination. However, both actresses reverse the source of pollution by constructing themselves as beyond the hypocrisy of society. They are pure victims who credulously imbibe men’s ‘poison believing it to be nectar’. They receive the destructive force of public life in the same way that nationalists describe the intoxicating influence of the English on the Bengali psyche. Unlike the Bengali male intellectual, prostitute-actresses did not have the option of separating themselves from the taint of sex. Instead, Binodini embraces her status as ‘polluted’ and uses it as a justification for her retort; ‘Like my own tainted and polluted heart, I have tainted these pure white pages with writing. But what else could I do! A polluted being can do nothing other than pollute!’

The contaminating threat of the prostitute-actresses who were Shakespeare’s first Bengali hostesses was eventually erased by the introduction of ‘respectable’ women to the stage by Tagore in his 1927 production of Natir Puja, a drama that featured an all-female cast composed of his students at Santiniketan. Aishika Chakraborty argues that ‘Tagore’s foremost contribution was to provide the context for the emergence of “respectable” middle-class women in the world of performing arts, the stamping ground of “unrespectable” public women.’ This stamping out of the ‘unrespectable’ by ‘respectable’ society might explain why Shakespeare’s original Bengali hostesses do not prominently feature in the accounts of Bengali theatre historians.

The first Bengali actresses of Shakespeare made traditional ideals exciting and illustrated the dangers of ‘bad’ women to the benefit of a burgeoning Bengali theatre. Like the first Bengali male actor to play Othello, the controversy around their employment as objects of scandal and spectacle drew crowds. However, in contrast to the monolithic spirituality emphasised in the Bengali male’s literary responses, Bengali Shakespearean actress’ materiality was a concrete and undeniable testament to the heterogeneity of female existence. Their proximity to the coloniser’s text required an existence between the spiritual and the mercenary that blurred the binaries between angel, whore, bhadra, abhadra, Bengali and English. The contradictions between the celebrated characters on-stage and the lives of these actresses outside societal protection were kept out of focus. Perhaps the threat posed by the conflicting roles of these women in the face of an imagined feminine ideal is the reason they have been forgotten when it comes to remembering Shakespeare as Bengal’s sublime guest.

We do know that she played Kalpalkundala, Bankim Chattopadhyay’s Miranda/Desdemona composite, and we have her pictured ‘in the role of Cleopatra’ (as seen in the top photo heading this page). Binodini was also a prolific writer, unique in that she left detailed descriptions of the process of acting, including the impact of Shakespeare on her craft—though not explicitly through playing a role. Rimli Bhattacharya’s translations of Binodini’s Amar Katha (My Story, 1912) and Amar Abhinitri Jiban (My Life as an Actress, 1924-25) are invaluable resources for tracing this influence. Binodini’s only education came through the theatre. Binodini’s recollections illustrate the role of Shakespeare in the relationship between director and actress:

"I liked very much the stories narrated by Girish-babu about famous British actors and actresses and whatever else he read out to us from books: He explained to us the various kinds of critical opinions expressed about Mrs. Siddons when she had rejoined the theatre after being married for ten years. He even told us of an actress in England who practised her notes with the birds in the forest. I was also told about the costume that Ellen Terry wore; how Bandmann dressed in his role as Hamlet; how Ophelia always wore a dress made of flowers. [He would] talk to us about numerous English actresses and the works of famous English poets such as Shakespeare, Byron, Milton and Pope. He discussed their works in the form of stories and sometimes he read out sections from the texts to explain them better. […] I would be anxious to see the performances of any famous British actor or Actress who happened to come to the city. […] When I came back home after the performances, Girish-babu would say, “Well now, let’s hear something about what you’ve seen.”

We see the actress’s delight, as a pupil, in being introduced to Shakespeare’s ‘stories’ but also her anxiety about performing roles in the ‘English’ way. Mrs. Siddons appears yet again in the psyche of the Bengali hostess as a model of perfection but this time as a warning against leaving the theatre in pursuit of domestic life. Most importantly, the reflection reveals the fact that Binodini was respected enough by her mentor to be asked her opinion on Shakespearean performances. Binodini was invited to view and review the work of the ‘greatest’ poet played by the English masters of her Bengali masters. Such power fuels the traversal of the threshold between actress and writer. Contact with Shakespeare facilitates Binodini’s trajectory from the realm of female object into that of masculine authority.

Binodini relished the ‘power’ and ‘intoxication’ of life on the Bengali Shakespearean stage. Binodini’s description of her first encounter with the stage reverberates with an almost sexual ecstasy:

"When I saw before me the rows of shining lights, and the eager excited gaze of a thousand eyes, my entire body became bathed in sweat, my heart began to beat dreadfully, my legs were actually trembling and it seemed to me that the dazzling scene was clouding over before my eyes. […] Along with fear, anxiety and excitement, a certain eagerness too appeared to overwhelm me. How shall I describe this feeling?"

Binodini was at first overwhelmed by the sublimity of the ‘dazzling’ lights ‘clouding over’ her. However, from her position after the end of her career, in a place of isolation and poverty, the memories of the Theatre have become both her ‘closest companion to the last days of [her] life’ and an ‘addiction’ that she struggles to describe:

"Well, I have the desire. But what powers do I possess? And what shall I speak of? What to say and what not to? How little I know! From time to time I come to see performances. What an addiction it is! As if the theatre beckons to me from the midst of all other work. I look at all the new actors and actresses, educated, refined and elegant, so many new plays, the spectators, the applause, the commotion, the hubbub and the footlights. One scene follows another and the bell rings as the curtain falls—all this and so much more comes back to my mind!"

Like Bengal’s silent coconut groves leaning towards the powerful sun, she is drawn to the memory of the stage by ‘desire’. She embraces the ‘addiction’ that is the theatre, welcoming the deflowering ‘gaze of a thousand eyes’. Her powerful literary description carries with it all the tumult of the ‘the applause, the commotion, the hubbub’ of the moment when ‘the bell rings and the curtain falls’. Despite the effectiveness of her writing, she questions ‘what powers do I possess?’ The guilt of abandoning ‘all other work’, including respectable, private, and silent service to society, in order to describe her ‘addiction’ is expressed through a deep anxiety about both the moral implications of her profession and her supposed inadequacy as a writer. As Bhattacharya observes, Binodini calls her story a ‘narrative of pain’ due to its content as well as the frustrating process of putting ‘ink’ to ‘paper’. Writing, unlike acting, is uncharted territory for the public woman and the process of navigation is agonising at times. A tragic femininity appears in Binodini’s construction of herself as an ‘addict’ and a victim of public life, limited in her writing by her status as an abhadra woman but powerful in her trangressions onto the stage and page.

The tension between Binodini’s transgression of gender-roles and the imposing borders of the male picture-frame is encapsulated by her embodiment of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra. Like Binodini, Cleopatra has been called a ‘supreme actress’, playing the roles of both exotic seducer and faithful wife. Binodini’s known parts ranged from Brittania herself to stereotypical Hindu wives. She was at the centre of a tug-of-war between different femininities—at one end, the westernised prostitute, and at the other, the Hindu domestic fairy. She describes the contradictions of her existence and the confusion it caused her when forming her own identity. On playing the ‘lady of gold’, Kanchan, who seduces the married protagonist of Sadhabar Ekadoshi at the same time as the innocent victim, Kunda, from Bankim's Bishbriksha, she writes:

"What a world of difference (between the two roles) whether in terms of their nature or in terms of the dramatic action. It would be impossible to describe the innumerable selves into which one must divide oneself while acting. As soon as one brought to completion a particular bhava, one was obliged to immediately summon another. This had become natural to me. Even when I was not acting, I would forever be immersed in a different bhava."

In Sadhabar Ekadoshi, the cheating husband’s wife is described as ‘a fairy at home’ and ‘such a precious Sita at home’. The man describes Kanchan as her material and sensual opposite; ‘I’ve put Kanchan-moni, the chief thing in town, on my crown.’ Binodini’s rapid shifts between the bhavas of angel and whore mirror those of Cleopatra who is sometimes a foreign object, sometimes the goddess Isis, and sometimes “no more than e’en a woman”. Cleopatra, as a ruler, is a public woman, trespassing into the realm of masculine authority. A similar array of roles multiply for Binodini as she takes up the male author’s pen and tries to define herself.

Binodini’s final position as a confused social anomaly directly opposes the temporary comfort of social acceptance Binodini attained at the height of her career, when she was blessed by one of Bengal’s most influential religious men while playing a man’s role. In 1884, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda’s guru and one of the most famous saints of the nineteenth-century, visited the Star Theatre. Binodini was playing the role of Chaitanya, an ancient saint whose name means ‘Consciousness’. Binodini describes an encounter between herself and Ramakrishna that made Bengali history:

"it was during this performance of Chaitanya-Lila, that is to say, not only this performance, but the incident around it which became the source of greatest pride in all my life, that I a sinner, was granted grace by the Pramahansadeb SriRamakrishna mahashoy. Because it was after seeing me perform in Chaitanya-Lila, that the most divine of beings granted me refuge at his feet. […] cleansing with his touch my sinful body, he blessed me, “Ma, may you have Chaitanya!” Poignant indeed was the sight of his gentle and compassionate image before an inferior creature such as myself. The Patitpaban himself was reassuring me, but alas, I am truly unfortunate; even so I have been unable to recognise him. Once again, I have been ensnared by temptation and illusion and made my life a veritable hell."

By calling Binodini ‘Ma’, Ramakrishna asserts his view that all women are mothers and ‘cleanses’ her of sexual pollution. Yet the blessing, ‘may you have Chaitanya’ welcomes her into the realm of male reason. By playing the role of a male saint, Binodini was able to approach this power in a socially sanctified manner. The emphasis on her role as a chaste Hindu was so intense that Binodini ‘unsexed’ herself, both by becoming a man on-stage and by intellectually duplicating Ramakrishna’s ideology.

The transformation was, however, only temporary and firmly in the hands of male viewers and benefactors. Binodini’s guilt at having once again become ‘ensnared by temptation and illusion’ refers to her status at the time of writing as a poor woman. Having been thrown out of her house after her husband’s death, Binodini had to return to the ‘sin’ of commerce to survive. Paradoxically, Binodini becomes a virginal mother-figure through male impersonation, an act of transvestism that Cleopatra also uses to exercise authority. While Cleopatra’s rebellious transvestism recalls the monstrous hybridity of Lady Macbeth and prostitution, Binodini’s role is sanitised by the fact of Girish’s influence, Ramakrishna’s praise, and the spiritual character of Chaitanya. The play depicts Chaitanya’s renunciation of the domestic sphere in pursuit of an even more ideologically restricted space of religious retreat. Binodini’s controversial status as a prostitute-actress made the ancient virtues of sacrifice and godliness that Chaitanya represents exciting and new, achieving on stage what Bankim had achieved in his Miranda/Desdemona composite in Kapalkundala.